Draining California’s Heartland: The Hidden Agenda Behind the Potter Valley Dam Removal

PG&E’s decommission plan isn’t about fish—it’s about politics, land, and control.

California, long known as America’s agricultural powerhouse, is under siege from policies that threaten the very foundation of our food system. Governor Gavin Newsom has advanced measures that, whether by design or consequence, will strip farmland from private farmers, bankrupt small operations, and reallocate land for purposes ranging from identity-driven redistribution to massive renewable energy projects. While these policies are being framed as environmental progress, their real impact is the dismantling of rural livelihoods and the destabilization of food security not only in California but across the nation and beyond.

This is not about abstract policy. It is about the farmers, ranchers, ecosystems, and communities that are being directly affected. From the dismantling of the Klamath dams—hailed by Newsom as a “world model” even as it killed hundreds of thousands of Chinook salmon—to the looming destruction of the Potter Valley Project, we see a repeated pattern: decisions made under the guise of “saving fish” or “restoring habitat” that instead devastate wildlife, wipe out family farms, and empower powerful stakeholders with little regard for the people or the environment.

Let’s examine what is happening in Potter Valley, where farmers woke up last summer to find their water shut off. I will share insights from Dr. Rich Brazil, a veterinarian and chairman of Save the Potter Valley Project https://www.savepottervalleyproject.org, whose community is on the front lines of this fight. Along the way, I will provide context—facts that expose the hypocrisy of these policies, the science that contradicts their justification, and the larger forces at play.

What is happening in California is not an isolated story. It is part of a broader war on farmers and on the people who depend on them for food. If we fail to recognize this now, we risk losing not just farmland, but an irreplaceable way of life.

Testimony from the Front Lines

Dr. Rich Brazil, a large-animal veterinarian and ranch management consultant, has lived and worked in Potter Valley since 1988. Together with his wife, also a veterinarian, he built both a practice and a family in this remote Northern California community. For more than three decades, he has witnessed firsthand how the Potter Valley Project transformed a rugged mountain valley into a viable agricultural hub. The century-old diversion system, constructed by Pacific Gas and Electric (PG&E), has long provided the lifeblood of the region: reliable water for homes, pastures, crops, and livestock.

That lifeline is now under imminent threat. PG&E has formally filed with the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) to decommission the Potter Valley Project. Should the removal proceed, irrigation and water storage that sustain not only Potter Valley’s 1,500 residents but also as many as 600,000 to 750,000 downstream users in Mendocino, Sonoma, and Marin counties would be eliminated. Without storage capacity, hydrologists estimate that half the time the Russian River would effectively run dry, cutting water supplies to farms, municipalities, and domestic households alike.

Dr. Brazil chairs Save the Potter Valley Project, a grassroots organization formed to oppose PG&E’s decommissioning. He warns that the summer’s water shutoff—implemented abruptly under the pretext of protecting fish habitat—was merely a preview of permanent scarcity. “What happened to us,” he explains, “is what everyone downstream will soon face once the dams are gone.”

Broader Impacts

The potential loss of this project extends far beyond irrigation. Marin County, one of California’s wealthiest regions and just north of San Francisco, receives roughly a quarter of its water supply from Sonoma County. The city of Novato depends on Sonoma for an estimated 75% of its water. In effect, dismantling the Potter Valley Project threatens the municipal supply chain of three counties, with consequences ranging from rising water costs to outright shortages during drought years.

For Potter Valley itself, the impact is existential. A community built over a century around the stability of irrigation water now faces the prospect of economic and demographic collapse. What began as a hydroelectric project has evolved into the foundation of an entire regional economy. Farms, ranches, and small towns are inseparably tied to the system’s continued operation. To remove it, locals argue, is not environmental restoration but economic sabotage.

Political Calculus

Dr. Brazil suggests that the decision to decommission the dams is less about ecological science than political expediency. PG&E, although technically a private company, is in practice a regulated monopoly whose rates and profits are tightly controlled by the California Public Utilities Commission (CPUC). The CPUC, in turn, is composed of commissioners appointed by the governor. “Ultimately,” Brazil observes, “PG&E survives by keeping Governor Newsom happy.”

The timing of PG&E’s reversal on Potter Valley raises further questions. Prior to the catastrophic Paradise fire of 2018, the utility had invested in repairing diversion tunnels and appeared committed to maintaining the project. After the fire, however, PG&E entered bankruptcy and emerged only after securing a $21 billion bailout under Assembly Bill 1054, legislation strongly backed by Newsom. In the wake of that deal, PG&E’s posture shifted sharply—toward decommissioning the Potter Valley Project and other dams, while simultaneously lobbying for state and federal subsidies to keep Diablo Canyon, California’s last nuclear power plant, in operation.

This apparent contradiction, Brazil argues, underscores the broader strategy: dismantle existing hydroelectric systems that provide water security for rural communities while redirecting public resources toward politically favored renewable energy projects. The abandoned Ivanpah solar project in the Mojave Desert, which collapsed after consuming more natural gas than it produced in solar power, illustrates both the risk and the cost of this shift.

Water Management Versus Environmental Optics

Supporters of dam removal frequently frame their efforts as necessary to “save the fish” and restore free-flowing rivers. But testimony from Dr. Rich Brazil, combined with decades of flow data, paints a different picture. The Potter Valley Project was designed not only to generate hydropower but to regulate seasonal flows in a region with a Mediterranean climate—rain from October to April, followed by months of near-zero precipitation.

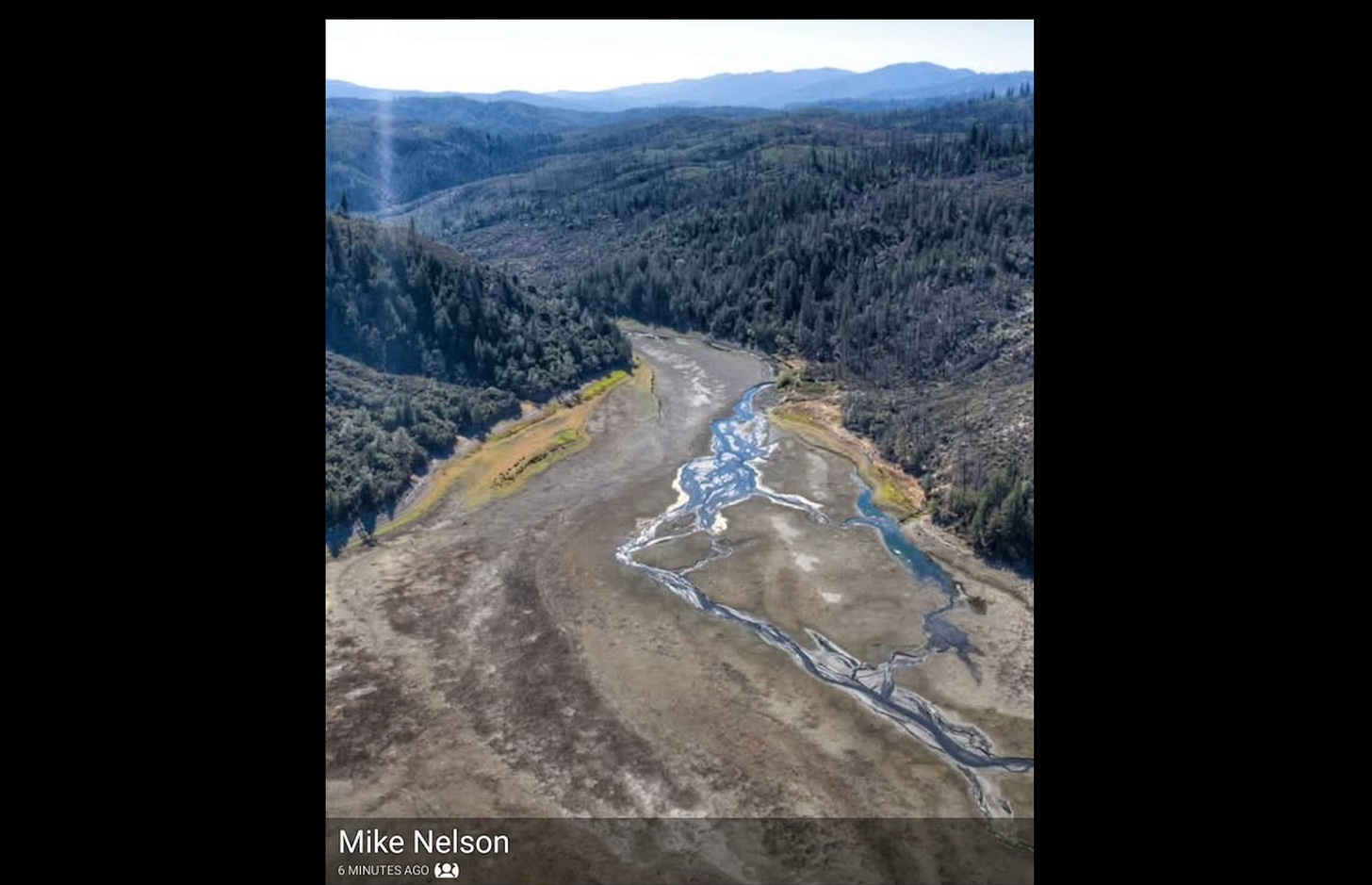

Eighty percent of the water stored in Lake Pillsbury bypasses the diversion and continues downstream to the Eel River, where it sustains summertime flows. Without that storage, the Eel’s headwaters produce as little as one to ten cubic feet per second during dry months—far below the 20–40 cubic feet per second that federal licenses require to support fish populations. The regulated releases from Lake Pillsbury are not a threat to salmonids; they are their lifeline.

This contradicts the narrative advanced by state officials and advocacy groups. As Brazil notes, decades of progressively reduced diversions under a 2002 National Marine Fisheries Service “biological opinion”—down 60 percent by 2006, now down 80 percent since 2020—have yielded no measurable rebound in fish counts. Eliminating the remaining diversions, he argues, will not benefit salmon but will instead silt up spawning beds for decades as 40 million cubic yards of accumulated sediment flushes downstream.

A Century of Infrastructure

Brazil also traces the project’s origins to a moment of early-20th-century ingenuity. In 1905, engineers recognized a 450-foot fall between the upper Eel and the nascent Russian River system near Potter Valley. By 1908, mule teams had completed a diversion tunnel that channeled water downhill to generate inexpensive, renewable electricity. Within years, a second dam—Lake Pillsbury—was added to ensure year-round flows in a climate of winter floods and summer droughts. Over time, the project evolved from a private power venture into a regional water security system sustaining farms, ranches, and municipalities across three counties.

Removing this infrastructure now, Brazil warns, would reverse more than a century of adaptation. “We have no water in these rivers in the summertime without some source of reservoir,” he says.

Political Influence and Stakeholder Exclusion

The push to decommission the Potter Valley Project also raises questions about governance and transparency. Governor Gavin Newsom publicly pledged in January 2024 to remove both Cape Horn and Scott dams—assets owned by PG&E. Yet state officials have simultaneously excluded Potter Valley residents, landowners, and local tribes from the “stakeholder” process that will determine the dams’ fate. In their place, advocacy groups such as California Trout and Trout Unlimited—beneficiaries of sharply increased donations from PG&E shareholders—have been elevated as stakeholders, along with a downstream tribe that stands to be paid for dam removal but is not directly affected by the river.

Financial records show that Vanguard Charitable, associated with one of PG&E’s largest shareholders, increased its grants to California Trout by more than 300 percent between 2022 and 2024, peaking at $347,000 in the latter year. JPMorgan Chase, another major PG&E shareholder, has also supported these organizations, and PG&E itself has sponsored their fundraising galas. None of this proves illegality, but the optics—advocacy groups pushing a policy that benefits the very shareholders funding them—are difficult to ignore.

The Safety Narrative

Another key argument for removal—that the dams are unsafe—is also disputed. Scott Dam received perfect “five out of five” safety ratings until 2019–2020, when PG&E began citing vague seismic concerns. Subsequent FERC correspondence revealed no documented threat to the dam’s structural integrity; in fact, an uncovered report stated the dam was “suitable for continued safe and reliable operation” for an estimated 850-year window. Yet under political pressure, water levels were lowered by ten feet and PG&E ceased pursuing further testing, stating it no longer wished to keep the dam.

For critics like Brazil, this sequence of events—Newsom’s campaign promises, PG&E’s $21-billion bailout under AB 1054, the abrupt reversal on dam policy, and the transfer of $532 million in decommissioning costs to ratepayers—resembles a “quid pro quo” more than environmental stewardship. “They’re a private company when it suits them,” he observes, “and not a private company when it suits them.”

Exclusion of Stakeholders and the Assault on Property Rights

The process by which PG&E and the State of California are moving toward dismantling the Potter Valley Project has been as contentious as the outcome itself. From the beginning, the “stakeholder group” formed to evaluate the project’s future was tightly controlled. Under its charter, the admission of new stakeholders required unanimous approval. When Lake County requested inclusion—citing its direct interest in purchasing or co-purchasing the project’s assets—California Trout (CalTrout) vetoed the proposal outright. By design, the process was structured not to seek a buyer or preserve the project, but to ensure that dam removal remained the only viable outcome.

This exclusion highlights a fundamental paradox: those who actually own property, depend on the project for water, or reside in the impact zone were systematically denied representation, while outside nonprofit groups and advocacy organizations were elevated to decision-making power. For residents like Dr. Rich Brazil, this represents not participatory democracy but a collectivist maneuver—one that overrides private property rights and silences local voices in favor of politically connected NGOs.

Legal Precedent and FERC’s Role

Proponents of removal have claimed that PG&E, as a private company, retains the right to dismantle its own infrastructure. Yet precedent complicates this claim. In American Whitewater v. FERC, a case in federal district court, FERC determined that maintaining an existing dam, even after decommissioning, served the public interest. The court upheld FERC’s position. That ruling underscores that hydropower projects are not merely private property; once licensed and integrated into a regional water system, they carry obligations to the public.

FERC is designed as an independent agency under the Department of Energy, insulated from political influence. Yet in practice, its recent actions suggest alignment with state pressure. In 2024, the agency approved the abrupt summer cutoff of Potter Valley diversions with no warning to farmers who had already planted crops and invested in inputs. Independent flow projections showed that diversions could have been modestly reduced while still preserving both fish habitat and wildfire reserves. Instead, FERC approved a complete shutoff—raising doubts about whether the agency weighed the broader public interest or yielded to external advocacy campaigns.

Ecological Trade-offs: Fire, Wildlife, and Elk

The ecological consequences of removing Scott Dam and draining Lake Pillsbury extend far beyond fish populations. The reservoir, located within Mendocino National Forest, is the region’s primary source of water for wildfire suppression. Twice in the past eight years, it has been instrumental in containing two of the largest wildfires in California history, one of which burned over one million acres. Without Lake Pillsbury, that resource vanishes—leaving millions of acres of timberland and nearby communities more vulnerable to catastrophic fire.

Wildlife faces similar risks. For over 50 years, the state has managed a Tule elk herd at Lake Pillsbury, now numbering in the thousands. In 2024, the California Department of Fish and Wildlife acknowledged in its hunting regulations that dam decommissioning would destroy this habitat. The agency subsequently petitioned to triple antlered elk harvests and double antlerless harvests, effectively planning for a 90 percent population reduction to pre-empt starvation. For locals, the irony is stark: under the banner of protecting salmon, the state is actively preparing to eliminate one of California’s most iconic and once-endangered big-game populations.

The Politics of Optics

Dr. Brazil notes the contradiction at the heart of state policy: dismantling infrastructure that provides clean, renewable hydropower while California simultaneously pledges to achieve carbon neutrality by 2030. The Potter Valley Project’s annual operating costs, roughly $578,000, are dwarfed by the $1.9–2 million in electricity value it still produces under reduced flows—not to mention the $30 million in potential annual revenue from water sales downstream. By contrast, decommissioning is expected to cost ratepayers at least $500 million, leaving nothing in return.

Why pursue such a course? Critics argue the answer lies in political optics. For Governor Newsom, positioning himself as the leader who restored the Eel River and created the nation’s “longest free-flowing river” provides a potent narrative ahead of a potential 2028 presidential campaign. The ecological and economic consequences—ranging from destroyed elk herds to ruined farmland—are abstract to urban voters but politically advantageous as symbols of environmental achievement.

Land Transfers and Energy Economics

The broader pattern reveals more than optics. California has launched programs to buy back devalued farmland—land stripped of water rights—under the justification of reallocating it to minority or indigenous groups. Simultaneously, PG&E profits more from solar and wind projects than from legacy hydroelectric dams. With an aging farm population and an anticipated generational transfer of property over the next decade, critics see a strategy emerging: use policy to devalue farmland, acquire it through state or corporate channels, and repurpose it for renewable energy projects or government-directed redistribution.

In this context, dam removal is not simply about fish or rivers. It is about reshaping land ownership, consolidating control of water, and redefining the economic base of rural California.

Consequences for Agriculture and Communities

The abrupt cutoff of Potter Valley’s irrigation water in the summer of 2024 served as a grim preview of what lies ahead if the Scott Dam is removed and Lake Pillsbury drained. Farmers who had already planted crops—investing in seed, fertilizer, labor, and fuel—were left without the water necessary to sustain them. Orchards and vineyards, cornerstones of the regional economy, were denied essential post-harvest irrigation, leaving trees and vines stressed going into winter. Irrigated pastures dried prematurely, forcing cattlemen to feed hay months earlier than planned, dramatically raising costs in a business already teetering on thin margins.

For many families, the consequences reached beyond their fields. In this arid valley, irrigation also sustains the aquifer. Domestic wells, which many households rely upon for drinking water, require recharge from regular irrigation cycles. With diversions halted, families reported dropping water tables and growing uncertainty about the safety of their domestic supply.

The wider ramifications stretch far downstream. Sonoma and Marin counties—together serving more than 600,000 residents—depend on Potter Valley diversions to stabilize the Russian River. Projections show that without this supply, the river will run dry half the time in normal years, and even more frequently during droughts. Municipalities may face water shortages, rationing, or skyrocketing costs, but for agriculture the outcome is terminal: the loss of permanent crops, the collapse of livestock operations, and the destruction of a century-old rural economy built around this water.

The Ecological Irony

Farmers argue that the policy is not only economically ruinous but ecologically shortsighted. By removing Lake Pillsbury, the state eliminates the region’s primary reservoir for wildfire suppression—despite the fact that two of the largest wildfires in California history were contained using its waters. Habitat destruction compounds the crisis: managed elk herds, migratory waterfowl, and countless other species that have adapted to the altered ecosystem will suffer or vanish outright.

As one rancher put it: “They talk about restoring the river to what it was, but that river hasn’t existed for a hundred years. What exists now is a living, breathing ecosystem that supports farms, ranches, wildlife, and people. That’s what they’re destroying.”

Social and Cultural Loss

The removal of the Potter Valley Project does not merely threaten crops and cattle. It threatens the very fabric of the community. Farms that have been handed down for generations will become unsustainable. Property values will collapse as wells run dry and irrigation becomes impossible. Families who have stewarded this land for decades—or in some cases since before the project was built in 1908—face displacement.

The human toll is already visible. Parents question whether their children can inherit land that no longer produces. Local businesses tied to agriculture brace for collapse. And with every acre lost to viability, the likelihood increases that the land will be consolidated into state programs or converted to industrial-scale solar projects—an outcome that strips away not only livelihoods but the rural character of the valley itself.

Conclusion and Recommendations

The campaign to dismantle the Potter Valley Project is not about fish, safety, or economics. It is about political power, optics, and control. Governor Newsom and his allies in Sacramento have found a potent talking point in “restoring the longest free-flowing river in the nation,” but the cost will be borne entirely by rural Californians who lose their water, their land, and their way of life.

The evidence contradicts the official narrative.

The project is financially viable, generating millions of dollars in electricity and water value against relatively modest operating costs.

The ecological justification is inconsistent: salmon face multiple threats beyond the dams, while other species—elk, deer, waterfowl—will be devastated by the loss of the reservoir.

The public interest case is clear: more than 600,000 downstream residents and farmers rely on the diversions for drinking water, irrigation, and aquifer stability.

Farmers’ Position

From the farmers’ perspective, the Potter Valley Project is not simply infrastructure—it is survival. To strip it away is to force generational ranching and farming families off their land, dismantling a culture of stewardship that has preserved open space, wildlife habitat, and food security for over a century.

Recommendations

Federal Intervention: The Department of the Interior, USDA, and Congress should explore options for federal acquisition or grant support to allow local entities to purchase and operate the project. This would preserve both water and hydroelectric production while ensuring modernized fish passage facilities.

Independent Review: A comprehensive, independent ecological and economic impact assessment should be commissioned before irreversible steps are taken. This review must include wildfire mitigation, aquifer recharge, and downstream municipal reliance—not just fish habitat.

Stakeholder Reset: True stakeholders—farmers, ranchers, property owners, and local governments—must be granted formal seats in the decision-making process. NGOs with political agendas should not override the rights of those directly affected.

Transparency in Political Influence: The financial relationship between PG&E, the Governor’s office, and political donors must be investigated. The appearance that policy is being shaped by campaign contributions rather than public interest undermines both democracy and trust.

Balanced Energy Strategy: Rather than dismantling renewable hydroelectric infrastructure, California should integrate it into a diversified portfolio that includes solar and wind, avoiding the ecological destruction of wholesale dam removal.

Final Assessment

The Potter Valley Project represents more than a dam and a diversion. It is the backbone of a community, the anchor of an ecosystem, and a vital artery of California’s water supply. To sacrifice it for political theater and short-term optics is to betray the people who have sustained this land for generations.

This fight is not about nostalgia. It is about the survival of independent farmers and ranchers in Northern California—and by extension, the future of food sovereignty in the state.