Engineered Floods and Bought-Back Rivers: The Great Murray–Darling Land Grab

As governments flood paddocks in the name of saving rivers, farmers warn they’re the ones being drowned — in red tape, lost income, and broken trust.

Picture this: a broad stretch of river country winding through New South Wales, flat paddocks dotted with cattle, horses, lucerne, the odd windmill, and generations of farm families raising their kids under big skies. Now imagine that same land being told: “We need to raise the river flows. We may need to flood part of your property a few times a decade. We’ll pay you — hopefully. And we might buy more of your water rights, too.”

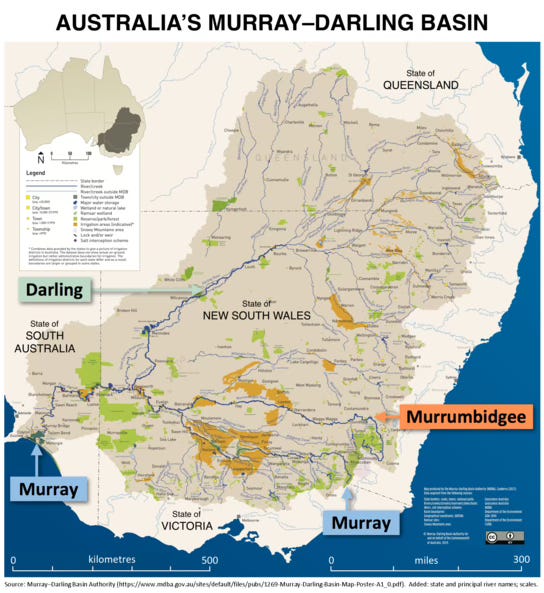

That is the latest chapter for farmers and ranchers in the southern basin of the Murray-Darling. And the question on the lips of many is: Is it necessary? And if so, at what cost?

What the governments are doing

Two major streams of policy are hitting the paddocks:

Water buy-backs.

The federal (and state) governments are reopening tenders to purchase irrigation water entitlements from willing sellers, under the umbrella of the Basin Plan recovery.

For example: a recent tender aimed at 44.3 GL (gigalitre — that’s one billion litres of water or in this case 44.3 billion litres) saw offers of over double that volume, as irrigators registered 88 GL+ across six valleys.

The stated goal: return more water to rivers, wetlands and flood-plains that have been squeezed by decades of over-extraction and climate stress.“Engineered floods” or increased environmental flows + flood easements.

On the southern side of the Basin (notably the Murrumbidgee River in NSW), the state government has gazetted a new maximum flow (up from ~22,000 ML/day to ~40,000 ML/day) as part of the Reconnecting River Country Program (RRCP).

This means more frequent (and larger) floods will be routed through flood-plain landscapes to recharge wetlands and ecological systems. To do that, the government is seeking flow‐easements on private land — legal rights for water to inundate parts of a property for defined periods.

The government is quick to say: “No compulsory acquisition of land — we’re seeking voluntary easements.”

Why it matters for farmers & ranchers

For someone working the land, these are not just abstractions. They translate into real-life risks, costs, and decisions. Let’s walk through the challenges:

Risk #1 – Property access and production disruption

When your floodplain gets designated for a high-flow event, paddocks can be cut in half, stock and machinery may be stranded, road or gate access lost — even if the inundation is a “designed” flood not a natural disaster. For example, landholders along the Murrumbidgee say they could face flooding “five years in every 10” under the new regime.

That means: days or weeks of lost production, crop damage, feed losses, extra fencing or infrastructure risk — and not all of this is yet clearly compensated.

Risk #2 – Compensation ambiguity

The government’s Landholder Negotiation Scheme (LNS) is meant to cover negotiation of easements and cost reimbursement (legal, valuation). But farm‐groups say the framework is still too vague.

Key questions: Who pays for the lost yield when paddocks are inundated? What if severed land means higher transport costs or less efficient operations? How long does the “flood event” count last? Farmers raise the point: “Even if we’re paid for easement rights, we still lose productivity that’s not directly calculated.”

Some landholders remain sceptical of the “voluntary” label, feeling pressured by the timeline.

Risk #3 – Community/region economic impact

When water rights are bought back in large volumes, irrigation communities worry about jobs, infrastructure, local services, towns that rely on agriculture. A Guardian article flagged fears of “wave of job losses” tied to resumed buybacks.

Smaller or remote communities may be less able to absorb shocks from loss of agricultural activity; ripple effects include schools, supplies, transport, seasonal work.

Risk #4 – Trust and property rights

Many farmers argue this is the thin end of the wedge: once you accept easements here, what comes next? One submission issues this warning: “A diabolical State government to consider implementing acquisition of easements over private land … which is an encumbrance on freehold.”

Given past disputes in the Basin (see the frequent complaints of mis-management and non-transparent processes), the trust gap is large.

Are the government’s arguments valid?

Weighing the other side: yes, there are legitimate ecological and long-term water‐security reasons. The question is how they’re being implemented.

For the policy:

The Basin Plan was designed to restore ecological health across one of Australia’s most important river systems. As a 2022 report noted: the promised 450 billion litres (to be recovered by 2024) was only 0.5 % delivered under past settings — a strong indicator the status quo was failing.

Environmental flows and occasional flooding of floodplains are natural processes that rivers and wetlands need. If you dam, divert or manage every drop of water, the system degrades. Scientific literature points out that water governance in the Basin has struggled with climate adaptation and is still “managerialist and technocratic”.

The government says buybacks are voluntary and easements too; they say compulsory land acquisition isn’t the plan.

From the water‐banks: irrigators did come forward to sell water — the tender oversubscription suggests people believe there’s value in participating.

Against the policy (from farmers/ranchers and regionals):

The process so far is perceived as top-down. Landholders say the map has appeared, with limited explanation of how often, how deep, which parts of land, and what happens if impacts exceed modelling. For example: “Landholder negotiation scheme regulation is premature. It’s impossible to ascertain how property owners will be impacted.”

The economic consequences of large-scale buybacks are very real for regional towns. Loss of water = loss of production = fewer jobs, fewer services.

The “voluntary easement” narrative is eroded when a landholder says: “We feel under attack … this is government over-reach and we are under attack.”

Compensation frameworks may not cover indirect costs, repeat inundation costs, lost property value, or emotional/heritage loss of longstanding family farms.

So: is it necessary — and if yes, how should it be done?

Yes — in broad strokes, many of us agree the Basin needs repair. Climate change is reducing inflows; decades of irrigation, diversion, and regulation have altered flows, wetlands, ecology, floodplains. Ignoring it simply stacks further risk onto farmers too (drier seasons, unpredictable flood behaviour, fewer natural pulses). But the devil is in the design.

Best-practice approach (which could be more farmer-friendly):

Transparent, localised modelling. Landholders need clear maps, clear data: how often will my land flood? How deep? What’s the margin of error? Provide real scenarios.

Independent review of compensation. Not just the easement fee, but a full impact assessment: production loss, access cost, water table changes, infrastructure risk, even land value changes.

Flexible easement design. Rather than “flood 5 times every 10 years for up to 4 days”, consider tiered options, opt-out for high-risk land, localised micro-design. Build in “hardship clauses”.

Community and town resilience support. If buybacks proceed or flood easements reduce production, governments should commit to regional transition funds: skills, infrastructure, diversity, alternate opportunities.

Trust building & genuine consultation. Frequent town meetings, on-farm sessions, two-way dialogue, transparent data, even third-party mediators. Without trust, “voluntary” becomes coerced.

Adaptive review built-in. If we flood more often than predicted, or property damage is higher than estimated, revert or modify. The policy should say “we will come back and adjust”.

Separate buybacks from flood easements in explanation. Many farmers see these as packaged together and fear a downstream charge. Clarity on what is voluntary, what is required, what is state-worth and what is irrigator-worth is crucial.

What happens if we get this wrong?

Farmers and ranchers could end up holding the bag: fewer crops, lower yields, stranded land, rising input costs, while being paid only a fraction of the real cost.

Regional towns shrink. Services disappear. Family farms become nonviable and sell out. The community fabric — schools, pubs, transport, local industry — weakens.

Trust erodes not just in water policy but in government generally. That means cooperation on future policy (climate adaptation, infrastructure) collapses.

Ecological goals may still not be met (if downstream modelling is flawed) and then there’s scapegoating of farmers, more regulation, more backlash.

Conversely, if there’s meaningful design and fair cost-sharing, you could have a win–win: farmers paid to adjust operations, wetlands revived, climate resilience built, regional communities reasonably supported.

My wrap-up: checklist for the landholder

If I were talking to the bush folks over a fence at a muster, here’s what I’d tell you:

Look at the easement map now. Don’t wait for the knock on door. Where are you relative to the 40,000 ML/day route? What land is low-lying? Which paddocks could be cut off?

Crunch the numbers: What is your current yield from that land? What happens if it’s flooded 3-5 times in a decade for 5-20 days each time (the modelling being floated)?

Ask about comp-loss: The easement may pay you for “right to flood”, but will it pay you for the loss of production? For road/access repair? For stock-movement delays? For lost value?

Negotiate hard: treat this like any farm purchase/sale. Use your adviser, get your infrastructure valued, your business impact quantified.

Engage your community: Not just as individuals — the town, the district, the regional economy matters. Pool resources, talk with neighbours, stay vocal.

Stay flexible: If you can manage some land as a “flood-corridor” and retain other land for higher ground operations, that might be the strategic hedge.

Monitor the policy rollout: Are timeframes being pushed? Is there a backlog of negotiations? Are there “quiet” letters being sent? Keep records.

Final word

The Murray–Darling Basin is a bit like a massive, aging farm infrastructure: the pipes are leaking, the pumps are strained, the paddocks haven’t seen a decent natural flood in years, and the cost of doing nothing is mounting. But repairing it shouldn’t mean the people who’ve worked the land for generations get left on the side of the road.

What we need now is policy with heart and horsepower — where farmers and ranchers aren’t just “stakeholders” but partners; where environmental aims are matched by economic realities; where rural towns aren’t collateral damage.

Because at the end of the day, if we lose the farmers and we lose the ranchers, then restoring the river system means little if there’s no one left to tend the land beside it.