Green Houses are Illegal "Dangerous" Structures

How One Woman’s Dream to Feed Her Community Sparked a Bureaucratic Battle in Teller County

A Mountain Garden Under Fire

In the crisp alpine air of Divide, Colorado, where growing seasons are short and soil yields are often poor, one woman dared to build a solution. Virginia “Jenny” Loop, a resident of Teller County, envisioned a year-round greenhouse that would provide fresh, locally grown food for her neighbors—a modest but powerful attempt to bring food security to her small mountain town. But after investing more than $150,000 and months of labor into the project, Loop has been ordered to stop work, cease all commercial activity, and tear down her greenhouse.

At the center of the controversy is a sprawling 2,856-square-foot structure she believed would be legally protected under Colorado’s agricultural exemption and the 2019 Farm Stand Act. County officials disagree—and now, a passionate local grower finds herself fighting not just for a building, but for her voice, her rights, and her dream.

A Vision Rooted in Community

Loop’s idea wasn’t novel, but it was necessary. “We don’t have the climate here to grow much of anything outside for most of the year,” she told us in a phone interview. “So I built this greenhouse to give my family and neighbors access to fresh produce, even in winter. I wanted to be part of the solution.”

The structure itself is not a commercial storefront. It is a pre-engineered greenhouse kit placed on Loop’s five-acre residential parcel just outside Divide, designed for sustainable vegetable production and intended to support a small-scale farm stand or CSA-style distribution. “We have 127 families ready to receive food from this project,” Loop says. “It’s about food, not profit.”

But in the eyes of Teller County officials, her mission crosses a legal line. They claim she violated zoning regulations, lacked a building permit, and exceeded what’s allowable under a residential well and home occupation limits.

Timeline of Conflict

June 2024: Initial Green Light

According to Loop, her trouble began during site work in June 2024 when a Teller County code enforcement officer visited her property. “He asked what I was building. I showed him the greenhouse plans and cited Teller County Code §R105.2-12, which exempts agricultural buildings from needing a permit if used solely for agricultural purposes,” she recalled.

She says the officer reviewed the code and confirmed her interpretation: “He told me, ‘If it’s just a greenhouse for growing, no permit is needed unless you add electricity.’ I felt assured and moved forward.”

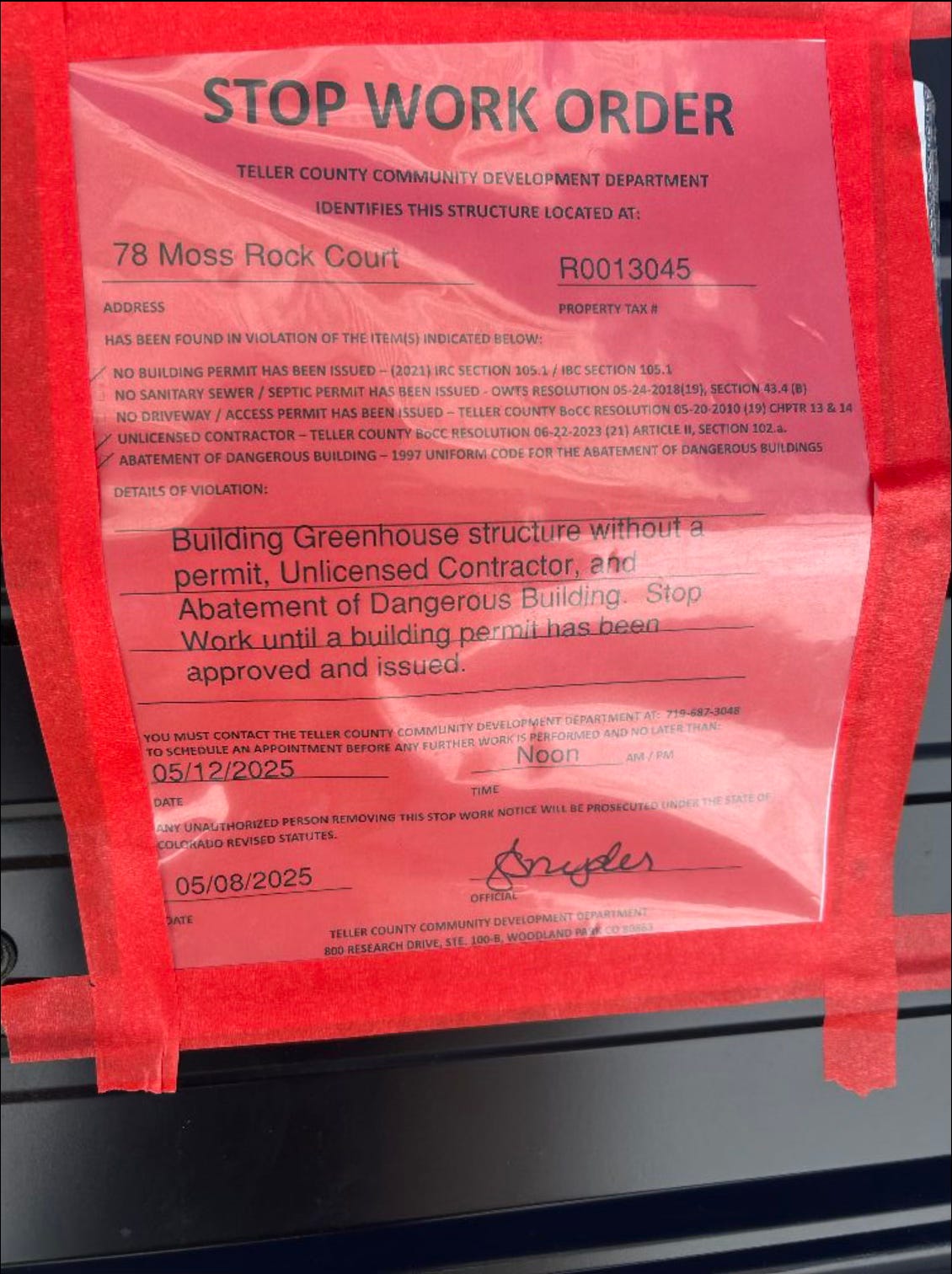

May 2025: Stop Work Order

After pulling and passing an electrical inspection in early May 2025, Loop was blindsided by a stop work order on May 8. “I was stunned,” she said. “I went down to the office the next day, documents in hand, expecting it to be a mistake.”

She presented the language from §R105.2-12 of the Teller County Building Code, which states:

“Work exempt from permit shall include agricultural buildings located in incorporated or unincorporated areas, regardless of zoning classification, provided the land is classified as agricultural by the County Assessor and setbacks are met.”

But that’s where the county drew the line: her parcel is zoned R-1 (residential) and is assessed as residential, not agricultural. According to Director of Community Development Dan Swallow, that means the exemption does not apply.

Bureaucracy Meets a Brick Wall

Loop describes the weeks that followed as a bureaucratic nightmare. “I called and visited constantly,” she says. “I spoke to multiple staff members, all of whom seemed unfamiliar with the agricultural exemption. They promised callbacks that never came.”

Finally, on May 28, she secured a meeting with Director Swallow. But the interaction, she claims, was anything but constructive.

“He walked in 20 minutes late, didn’t shake my hand, and said ‘What do you want?’ I tried to explain what had happened, that I was just following the code they published, but he interrupted constantly, told me to ‘get to the point,’ rolled his eyes, and slammed his hands on the table,” Loop said.

“I left that meeting feeling crushed. It wasn’t about interpretation anymore—it was about power.”

Loop says she was later called while driving and told by Swallow that he couldn’t find the code online, demanding she give him page numbers, despite having submitted the documents weeks earlier.

The Legal Crossroads

At issue is whether Loop’s greenhouse qualifies for an agricultural permit exemption under county code and whether it enjoys state-level protection under Colorado’s Farm Stand Act (HB 19-1191).

The County’s Position

Parcel is not agriculturally classified by the Assessor. The exemption only applies to land taxed as agricultural.

Zoning is residential (R-1) and does not allow commercial greenhouses or agriculture.

Greenhouse exceeds home occupation limits—it’s larger than the primary residence.

Domestic well use prohibits irrigation for commercial purposes.

Loop’s Counterargument

She relied on direct staff guidance and the published code which states zoning is not a disqualifier.

She is not operating a commercial greenhouse—she's growing food for neighbors, with no walk-in retail or advertising.

The Colorado Farm Stand Act preempts local restrictions and allows produce sales from a “farm stand” on parcels of any size, regardless of zoning.

She intends to seek agricultural reclassification through the County Assessor, which may retroactively validate the exemption.

What the Law Really Says

Colorado’s HB 19-1191 was passed in 2019 to prevent counties from using zoning laws to prohibit small producers from selling food grown on their land. The statute reads:

“A local government shall not prohibit a farm stand operated for the sale of raw and unprocessed agricultural products grown or produced on-site, regardless of parcel size.”

Though the law is clear on the right to operate a farm stand, it doesn’t directly address structures used for production—like greenhouses. However, if the greenhouse is part of the farm stand operation, as Loop argues, then state preemption may protect it from local enforcement.

“This is a narrow, but important point,” says Denver-based land use attorney Rachel Linn. “The law protects the operation, and a court may very well find that an accessory structure, essential to the operation of a legal farm stand, should be included under that protection.”

As for the building code, §R105.2-12 clearly allows exemption “regardless of zoning,” but it ties that exemption to assessor classification. “That’s a bureaucratic bottleneck,” Linn notes. “But if the land is in fact used agriculturally, she can petition for reclassification—and the county is arguably obligated to update it accordingly.”

A Bigger Question: What Is “Commercial”?

Much of Teller County’s position rests on the assertion that Loop’s use is “commercial,” which they claim is prohibited in residential zones. But that label is slippery.

“I’m not running a business,” Loop insists. “I’m growing vegetables and giving them to families. I’m not making a dime.”

In Colorado, the distinction between commercial and personal agriculture has become increasingly contested, especially in a post-pandemic era where food sovereignty and local production are rising priorities.

“We have to be careful,” says Colorado food policy advocate Jonathan Engler. “If you criminalize food-sharing as ‘commerce,’ you’re regulating kindness out of existence. And if state law says farm stands are legal on parcels of any size, then the spirit of the law should protect the entire operation.”

Where It Stands Now

As of July 2025, the county has ordered Loop to stop using the greenhouse, halt any on-site food sales, and remove the structure—or face fines and potential court action. Loop is exploring legal options, including:

Filing a Rule 106 appeal in district court,

Petitioning the County Assessor for reclassification,

Seeking a zoning variance or special use permit, and

Rallying public support and media attention.

She’s also written an open letter to the county commissioners, detailing her experience and calling for intervention. “I just want to grow food and help people,” she writes. “I didn’t expect to be treated like a criminal.”

In a statement to Yanasa TV Loop says she has tried classifying that portion of her land as agricultural since 2022.

“I have been working with the assessor since 2022 to reclassify my property as ag. Every time I checked their box... they moved the goal post on me! State law classifys agricultural land as "classified or elgible for classification" so I moved forward. The most important part is growing the food... I figured I would figure out the rest later.”

A Community Divided

Virginia Loop’s greenhouse may seem like a small issue in a small county—but it touches on much larger themes: the tension between local bureaucracy and state-level food sovereignty, the limits of property rights, and the treatment of residents who dare to dream of a more sustainable way of life.

Her case is now more than a zoning dispute. It’s a referendum on how communities interpret laws designed to empower local food production—and whether rural America still has room for the people trying to feed it.

As one of her neighbors posted on Facebook, “We need more people growing food, not more red tape. Let her grow.”