Supreme Court Declares No Right to Grow Food — Door Now Open for Farm Closures!"

Farming on Trial – Vermont’s Zoning-Farm Collision and What Comes Next

The Supreme Court Catalyst: Essex Junction Case

In May 2025, the Vermont Supreme Court issued a landmark ruling that redefined how farming is regulated at the municipal level. The case involved Jason Struthers, a resident of Essex Junction, who operated a small backyard duck farm and an outdoor cannabis garden. When the city moved to shut down his operations based on local zoning laws, Struthers pushed back, arguing that state law—specifically the Required Agricultural Practices (RAPs) and Right to Farm statutes—preempted municipal interference.

The Court disagreed. In its ruling, it clarified that:

Only farming practices tied to water quality, as defined under RAPs (such as manure management and buffer zones), are exempt from local zoning regulations.

All other aspects of farming—including structures, livestock numbers, odors, setbacks, and non-RAP cannabis activities—can be regulated by municipalities.

The decision overturned a lower court ruling and shattered the long-standing assumption that Vermont's agricultural activities enjoyed broad immunity from local zoning control.

Legal Landscape After the Ruling

The Vermont Supreme Court's 2025 ruling clarified which aspects of farming are protected from local zoning regulations—and which are not. Practices tied directly to water quality, such as manure management and vegetative buffer zones, remain shielded under the Required Agricultural Practices (RAPs). However, other common elements of farming operations are not protected. Structures like barns and greenhouses, the number or type of livestock, and cannabis cultivation that falls outside RAP guidelines can all be regulated by municipal zoning boards. Additionally, while farmers are protected from nuisance lawsuits regarding odors, noise, and dust under the Right to Farm law, those same impacts can still serve as the basis for zoning enforcement. This layered framework has introduced new legal exposure for farms operating in zones not designated for agriculture.

Vermont’s Right to Farm Law: What It Really Covers

At the heart of this controversy lies Vermont’s Right to Farm Law, codified in 12 V.S.A. § 5753.

What It Protects:

Agricultural operations in existence for at least one year;

That operate in compliance with state and local environmental laws, especially RAPs;

From nuisance lawsuits stemming from noise, odors, dust, or visual appearance.

What It Does Not Protect:

It does not shield farmers from zoning laws enacted by municipalities.

It does not override permitting rules, structural limitations, or bans on agricultural uses in designated districts.

While the law was designed to protect long-standing agricultural uses from encroaching suburban development, it was never intended to nullify a town’s authority to enforce zoning rules. Until the 2025 Court decision, however, many Vermonters believed it did.

Orleans Showdown: The Case of Tom Wood

Nowhere is the impact of the Supreme Court’s decision more apparent than in Orleans Village, where farmer Tom Wood finds himself at odds with the town’s zoning board. Wood has been operating a small livestock farm since 2016, raising pigs, goats, roosters, and chickens on property zoned mixed-use/high-density—a district where agriculture is not a permitted use.

History of Zoning Discussions

July 2024 Zoning Violation Issued to property owners.

November 2024 The violation was revoked.

December 2024 Town Voted to uphold the violation with a $100 per day fine.

Documents do not show what happened to the December violation.

January 2025 Pollock’s provide Wood with a Quit Claim Deed to the property.

May 2025 Supreme Courts Decision on Right to Farm Statutes

June 16th of 2025 Violation Filed Again

Following neighbor complaints about odor and animal welfare, the Barton zoning administrator issued a formal violation, stating the operation was out of compliance with zoning regulations. Wood appeared before the Barton Development Review Board (DRB) on July 23, 2025, in one of the first local-level tests of the Supreme Court’s new standard.

Based on photographs of Wood’s operations and testimony of neighbors, this particular agricultural operation did not seem to be operated in a clean and up to par. Yanasa TV did not uncover any evidence that animal cruelty or welfare charges have been filed against Tom Wood in relation to his livestock operation. While neighbors have voiced concerns—such as odor complaints and what they describe as mistreatment—local enforcement has focused solely on zoning violations, not animal welfare infractions. This suggests that animal welfare infractions may have not been justified.

Zoning enforcement often grows from public dissatisfaction. If neighbors are genuinely affected—whether by odor, livestock counts, or safety—those complaints can trigger zoning actions independently of welfare law. In fact, the zoning administrator has cited exactly this: Wood’s farm qualifies as an agricultural operation in a zone where that isn’t permitted.

It might seem that animal welfare laws would be a more direct tool to shut down a controversial livestock operation like Tom Wood’s. But in Vermont’s legal framework, it’s actually easier, faster, and more enforceable to pursue zoning violations than to mount an animal cruelty case.

Animal cruelty cases require documented neglect, veterinary evaluations, or eyewitness reports of abuse.

Zoning violations, by contrast, only require showing that an activity is occurring in a district where it’s not permitted—a much lower threshold.

Vermont’s animal cruelty statute explicitly exempts accepted livestock and poultry husbandry. So unless Wood was depriving animals of water, food, or shelter—or causing clear suffering—his farm would be protected from cruelty charges, even if neighbors find conditions unpleasant.

Zoning Is a Policy Tool, Not a Punishment

Unlike criminal statutes, zoning doesn’t require wrongdoing—it regulates land use, not behavior. This allows municipalities to:

Issue violations quickly with no police involvement,

Levy fines,

Demand removal of animals or structures without needing to prove harm,

Avoid the high legal burden of pursuing cruelty charges.

What the DRB Must Decide:

Does Wood’s farm meet the state’s legal definition of agriculture?

Do his practices fall within RAPs protections—or are they subject to zoning enforcement?

Legal Gray Area: Wood’s Property and the Limits of Grandfathering

A Sales Barn with History

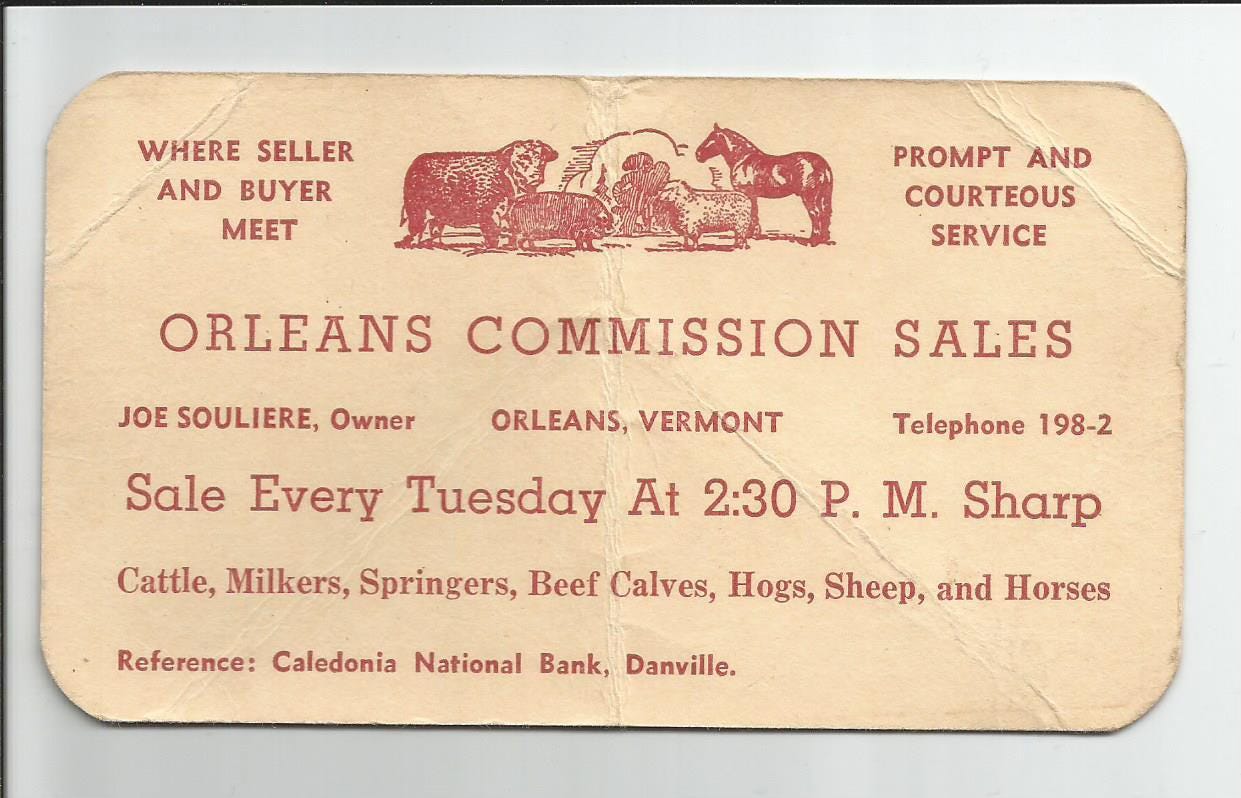

The property in question once served as a commission sales barn, a venue for livestock transactions and auctions—clearly agricultural in nature. But that use ended sometime before Wood’s 2016 acquisition. Yanasa TV has been unable to confirm the exact timeline. The Orleans Commission Sales business was owned by Joe Souliere, located in Orleans, and conducted sales of livestock including Cattle, Milkers, Springers, Beef Calves, Hogs, Sheep, and Horses.

The property was sold by Jean Souliere to Ronald and Brian Pollock in May of 2016 and reportedly leased to Wood in that same year.

In 2006, Orleans and Barton adopted a joint zoning bylaw that designated the area as mixed-use/high-density and explicitly excluded agriculture as a permitted use.

A 2019 Chronicle meeting report references smell complaints from animals at the site. A 2020 Barton Chronicle article states that officials were already looking for a "new use" for the old commission sales barn.

Can Prior Use Protect Wood’s Operation?

Under 24 V.S.A. § 4412(7), preexisting nonconforming uses may continue legally if:

The use predates the zoning change;

The use was not abandoned;

The new use is substantially similar to the old one.

While Wood’s property qualifies on the first count, there appears to have been a multi-year gap in agricultural activity prior to his ownership. That gap could be deemed abandonment, stripping away any “grandfathered” status.

Even if the nature of his livestock operation aligns in spirit with the former sales barn, differences in scale, animal types, or neighborhood character could lead officials to conclude that Wood’s use is not “substantially similar.”

Why Wood May Have Thought He Was in the Clear

When Wood started farming in 2016, he likely believed he was protected by Vermont’s Right to Farm law and longstanding agricultural norms. For eight years, he operated without challenge from local officials. This prolonged period of non-enforcement could bolster a legal defense rooted in laches—a principle that bars enforcement actions after excessive delay.

Courts weigh such claims cautiously, especially when public policy (like zoning compliance) is at stake, but it remains a potential argument in Wood’s favor.

Implications for Other Vermont Farmers

Regardless of what we may think of his operations the outcome will spread. The Tom Wood case and the Supreme Court decision send a clear message: municipal zoning trumps agricultural tradition in many areas of Vermont. Towns now have legal standing to:

Require permits for barns, fencing, and animal enclosures;

Enforce livestock limits in non-agricultural zones;

Deny new agricultural uses in neighborhoods previously considered rural by character;

Limit on-farm businesses like agritourism, workshops, or farm stands.

This creates a chilling effect for small, diversified farms, particularly in communities transitioning from rural to suburban.

Could This Alter Vermont’s Rural Identity?

Yes. Profoundly.

Vermont’s brand is built on its agrarian legacy. From cow pastures to cider presses, farming is part of the state’s identity. But if zoning boards begin limiting where and how agriculture can occur, that identity may slowly erode.

Rural gentrification could push farms out of traditionally mixed areas;

Loss of food sovereignty could increase dependence on imported goods;

Cultural friction between newcomers and long-time farmers may intensify.

Zoning Risk Across Vermont

No comprehensive database tracks how many Vermont farms are operating in zones that disallow agriculture. But anecdotal reports and land-use reviews suggest it’s a widespread issue:

Older zoning maps did not anticipate the modern rise of backyard agriculture or cannabis cultivation.

Many small farms and homesteads may already be out of compliance without knowing it.

As towns revisit their zoning maps post-Struthers, expect a surge in zoning violations, especially in rapidly developing areas.

A Legal Win for Agriculture: The Hartland Farm Store Case

While recent rulings in Vermont have tightened local authority over small-scale farms and homesteads, one case stands out as a rare legal victory for agricultural expansion. In June 2025, the Vermont Supreme Court ruled in favor of SM Farms Shop, LLC—a family-owned operation tied to the 600-acre Sunnymede Farm in Hartland—allowing the construction of a large farm store near Interstate 91. The decision affirmed that value-added agricultural enterprises, when properly aligned with regional and state planning objectives, can move forward even in the face of local opposition.

The dispute centered on whether the proposed store violated state land-use rules under Act 250, particularly the prohibition against "strip development" and inconsistency with town and regional plans. Despite concerns from the Hartland Planning Commission, the Supreme Court held that the project met Act 250’s criteria and was consistent with Vermont’s goal of supporting resource-based rural commerce.

The Hartland farm store case offers a compelling contrast to the more restrictive rulings in the Struthers duck farm and Tom Wood livestock cases, highlighting a more favorable legal pathway for agricultural development in Vermont. While Struthers and Wood faced local zoning crackdowns that restricted or denied their ability to farm, the Vermont Supreme Court upheld the right of SM Farms Shop, LLC to construct a farm-based retail outlet along a major highway corridor in Hartland. This approval was granted under the state's Act 250 land use permitting statute, which focuses on environmental compatibility and regional planning alignment, rather than the narrower constraints of local zoning bylaws.

A central reason for the Hartland project's success is how it was framed—not as a residential livestock operation or homestead, but as a commercial extension of an active agricultural enterprise. The farm store proposed to sell goods produced on the 600-acre Sunnymede Farm, making it a resource-based commercial use tied directly to farming. This distinction allowed the developers to argue successfully that the project met Act 250’s efficiency standards and did not constitute “strip development” under Criterion 9(L). Moreover, while the Hartland Planning Commission opposed the project on the grounds that it violated the town’s 2017 plan, the Court found that the town plan’s language was largely aspirational and lacked the specific regulatory force needed to override a compliant Act 250 application.

In contrast, the Struthers and Wood cases involved straightforward conflicts with local zoning laws. Both Essex Junction and Orleans Village had clearly defined land-use restrictions that prohibited farming in specific residential or mixed-use zones. With no Act 250 process involved and no ambiguity in the local ordinances, the courts sided with municipalities. These decisions underscored the limits of Vermont’s Right to Farm law, which only protects certain water-quality-related agricultural practices and does not exempt farms from zoning enforcement.

The Hartland ruling, however, provides a roadmap for farmers and rural entrepreneurs seeking to expand or diversify their operations legally. It suggests that value-added agricultural enterprises—such as farm stores, cheese shops, or maple product outlets—can succeed if they are thoughtfully integrated into regional development plans and presented as efficient, resource-based uses. It also reinforces the importance of using Act 250 strategically. While often viewed as a bureaucratic hurdle, Act 250 can offer a statewide permitting path that, if navigated correctly, circumvents restrictive local zoning.

Together, these cases reveal a split in Vermont’s approach to agricultural land use. On one hand, traditional, informal farming and homesteading—especially when located in residential zones—are increasingly vulnerable to municipal regulation. On the other hand, commercial agricultural development with regional economic goals and strong planning documentation may still find support through state-level oversight. The Hartland case suggests that Vermont’s farming future will depend less on long-standing cultural assumptions about the state’s farm-friendly image, and more on a farmer’s ability to understand and work within the evolving framework of land-use law.

Final Takeaway

Vermont’s farming future sits at a legal crossroads. The May 2025 Supreme Court ruling narrowed Right to Farm protections, handing municipalities new authority to restrict or eliminate farm uses. Tom Wood’s case in Orleans may soon become a precedent that reshapes how Vermont balances land use, local control, and agricultural tradition.

Unless lawmakers act to restore broader protections, Vermont farmers may discover that their rights depend less on soil health—and more on where their land sits on the zoning map.

All three cases—the Struthers duck farm in Essex Junction, the Tom Wood livestock farm in Orleans, and the SM Farms Shop in Hartland—collectively reveal a growing tension in Vermont between local zoning boards and the state’s long-standing agricultural identity. While Vermont has long celebrated its rural character, local governments are increasingly asserting zoning authority in ways that restrict traditional and small-scale agricultural activities. These cases expose a deeper shift: from a state once perceived as universally farm-friendly to one where farming rights now depend heavily on technical compliance with zoning codes, planning language, and regulatory procedure.

In the Struthers case, the town of Essex Junction aggressively enforced zoning restrictions to shut down a small backyard duck and cannabis operation, despite the owner's reliance on Vermont’s Right to Farm laws. The Supreme Court ultimately sided with the municipality, drastically narrowing the interpretation of agricultural exemptions and affirming that local governments have broad authority to restrict farm practices not explicitly covered by water-quality-focused RAPs (Required Agricultural Practices).

Similarly, in Orleans, the town of Barton pursued zoning violations against Tom Wood for operating a livestock farm in a residential zone, despite the property's agricultural history and nearly a decade of enforcement silence. Rather than addressing concerns through agricultural policy or animal welfare channels, the town chose zoning as its legal weapon—underscoring a pattern of land-use control overriding cultural norms and historical uses.

The Hartland case, while yielding the opposite outcome, still reflects this adversarial posture. The Hartland Planning Commission and regional planners attempted to block a farm-linked retail outlet that met state land-use goals under Act 250. Only a narrow 3–2 Supreme Court ruling preserved the project—revealing how even well-organized, resource-based agricultural development can face steep opposition from local authorities.

Together, these cases illustrate a broader trend: local zoning boards are becoming gatekeepers not just of development, but of agriculture itself. Their actions suggest a shift in priorities—from accommodating working landscapes to controlling land use for residential, aesthetic, or economic reasons that often conflict with traditional farming. Whether driven by changing demographics, gentrification pressures, or environmental politics, the result is the same: farming in Vermont now requires navigating a bureaucratic minefield, where tradition and legacy offer little protection without regulatory alignment.

This growing disconnect poses a serious challenge to Vermont’s agricultural future. If left unchecked, it could fragment rural communities, suppress local food systems, and undermine the very identity the state has long promoted. These legal battles are not just isolated zoning disputes—they are flashpoints in a much larger struggle over who gets to define the future of Vermont’s landscape.