Tyson Shutters Lexington — and Somehow the Middleman Gets Richer

How the Big Four Meatpackers Rig the Market, Crush the Rancher, and Laugh All the Way to the Bank.

What Tyson Just Shut Down — and What They’re Quietly Shrinking

Tyson didn’t just close a plant.

They pulled two major levers in the beef supply chain — one loudly, one quietly — and both land squarely on the backs of ranchers.

First, the headliner:

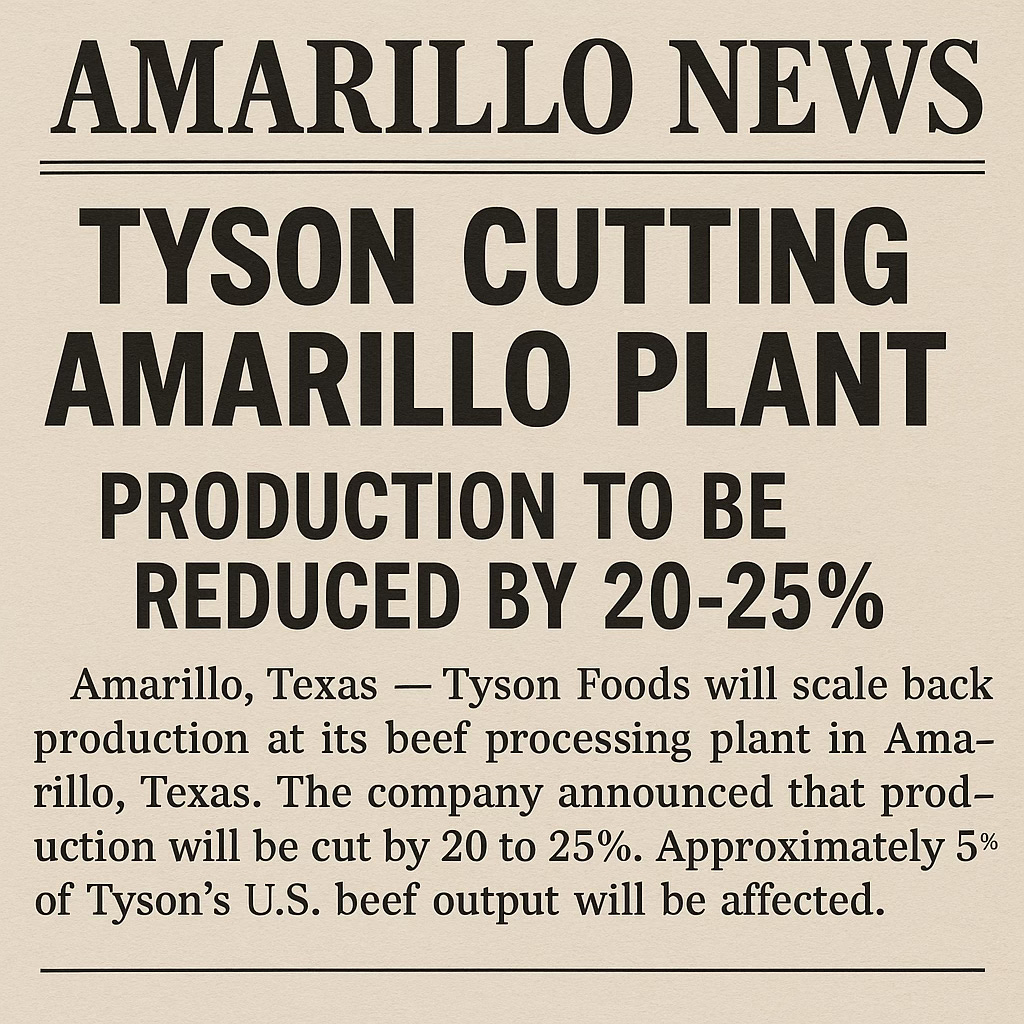

Tyson Foods is shutting down its Lexington, Nebraska beef plant, one of the largest in America. Roughly 5,000 head per day, 3,200 jobs, and an entire regional cattle market — gone. A facility that once kept Nebraska’s cattle flowing is going dark in early 2026.

Second, the “soft-landing” move:

The company is scaling down operations at its Amarillo, Texas facility to a single full-capacity shift. Not a closure, but a serious reduction — thousands of head per week evaporating from the system.

In one announcement, Tyson removed a major Nebraska slaughter hub and squeezed Texas capacity, shrinking the already-tight pipeline that moves cattle from ranch country to America’s meat counters.

You ever wonder why you’re paying twenty-five bucks for a ribeye… but the guy who raised the steer barely makes enough to cover feed?

Well, saddle up—because we’re about to talk about the real beef behind America’s beef.

And yes—President Trump just announced he’s coming after the Big Four meat packers. Finally, somebody in Washington found their branding iron.

Name one other industry where four companies can control 85% of everything that moves, set their own prices, write their own contracts, and then look you straight in the eye and say, “Relax, it’s just the market.”

That’s right—welcome to meatpacking in America. Tyson. Cargill. JBS USA—yes, the Brazilian-owned one—and National Beef. Together, they run the show. Ranchers raise the cattle. Packers raise the prices.

The problem: How the big meat-packers came to dominate and squeeze U.S. ranchers

Meet your adversary. These four mega-processors—Tyson Foods, JBS USA, Cargill Meat Solutions, and National Beef Packing Company—control roughly 80–85% of U.S. grain-fed cattle slaughter. When a handful of buyers dominate the market, the people who actually produce the beef—the ranchers—have about as much negotiating power as a steer at auction.

Even the USDA’s Economic Research Service admits that high concentration “could” affect producer prices. “Could”? That’s like saying gravity might pull you down if you jump off a hayloft.

The Levers of Control

Limited buyer options. Most ranchers can sell to only one or two packers within hauling distance. That isn’t a free market; it’s a one-stop monopoly with a loading dock. If most of the finished cattle in a region must go to one of a handful of packers, that gives those packers leverage over timing, delivery, quality specs, contract terms. Ranchers often cannot choose “my cattle go to a different packer” easily.

Procurement contracts & formulas. Most cattle now move under packer-written “alternative marketing arrangements” (AMAs) and formulas tied to benchmarks the packers themselves influence. Many producers don’t transact purely on a spot cash market; they are tied into alternative marketing arrangements (AMAs) or formula contracts based on grids, premiums/discounts and past price benchmarks. The packer side writes many of those formulas and grids — so the entity that dominates the buying side also shapes the terms.

Quality & grid control. Packers write the grids that determine premiums and discounts. Miss their specs, you eat the loss. Packers set yield/quality grids (for Choice vs Select, yield grade, trimming, dark cutters, etc.). When the majority of supply must meet those grids, it forces ranchers/feedlots to shape production (breed, feed, finish time) around what the packers want—and then absorb risk if they miss the specs.

Capacity bottlenecks. One plant fire or “maintenance weekend,” and bids dry up while grocery prices barely blink. When major plants go offline (e.g., fires, labor stoppages, pandemics) or when shackle/kill capacity is thin, packers have more power. They might slow purchases, delay delivery windows, or demand more concessions to secure slots.

Information asymmetry. Packers see real-time wholesale, export, and plant margins. Ranchers see a weekly report—and a prayer. Packers see wholesale boxed beef flows, export demand, plant scheduling, by-plant margins, etc. Many ranchers see only what they’re paid and general weekly market reports. That asymmetry enables the packers to act ahead of smaller players.

Simply Put, the spread between live-cattle prices and retail beef has widened. Consumers pay more, ranchers earn less, and the middle keeps the cream.

It’s not free enterprise—it’s corporate feudalism with refrigeration.

A History of Manipulation — Proven in Poultry, Denied in Beef

If history tells us anything, it’s that the meat industry has been caught red-handed before.

In 2021, Pilgrim’s Pride (owned by JBS USA) pleaded guilty to federal price-fixing in chicken and paid a $107.9 million fine. That’s not a rumor; that’s a conviction.

In beef, the modern giants haven’t seen criminal convictions—but they’ve faced a parade of civil antitrust suits. Result: tens of millions in settlements to consumers and ranchers—without admitting wrongdoing. Some cases were tossed on technical grounds, showcasing how hard it is for individual producers to prove collusion.

Courts and federal enforcers have proven illegal price manipulation in the poultry sector and have historically constrained packer power in beef through antitrust action. But when it comes to the modern beef giants, the story is murkier—no recent criminal convictions, but plenty of settlements and smoke.

In 2021, Pilgrim’s Pride—a major chicken processor owned by JBS USA—pleaded guilty to a federal price-fixing conspiracy and paid a $107.9 million fine. The company admitted that it colluded with competitors to coordinate prices and bids, directly harming farmers and buyers alike. That case was a clear, modern example of how corporate packers can and do manipulate food markets when unchecked.

The beef side has avoided such convictions—but not scrutiny. Over the past five years, Tyson, Cargill, JBS, and National Beef have all faced civil antitrust lawsuits alleging price coordination and market manipulation. Some of those cases have resulted in massive settlements—tens of millions of dollars paid to consumers and ranchers—without the companies admitting wrongdoing. Others have been dismissed on technical grounds, revealing how difficult it is for individual ranchers to prove collusion among billion-dollar corporations that dominate the market.

Historically, the federal government did act to break the grip of packers. In the early 20th century, the original “Big Five” meat companies were hit with a sweeping antitrust decree that forced them to divest non-meat holdings and restricted their trading practices. That landmark case shaped the Packers and Stockyards Act of 1921, meant to prevent exactly the kind of manipulation ranchers allege today.

A century later, concentration is back near record highs. Different names. Same game. The dynamics are the same: a few corporate buyers control the market, producers get squeezed, and every time prices diverge between the feedlot and the meat counter, it’s the packers who seem to profit most.

If Washington won’t fix the structure, there won’t be a next generation to take the ranch gates.

President Trump’s call for a Department of Justice investigation into the major packers could mark a return to those early antitrust roots. According to administration officials, the probe will examine whether the same structural power that once forced a breakup a century ago is again being abused—this time through data control, formula pricing, and coordinated procurement. If the DOJ finds that the big four are manipulating markets or restraining fair trade, it could trigger the most significant enforcement action against U.S. meatpackers in decades.

For ranchers, that investigation isn’t just political theater—it’s hope. It represents the possibility that Washington might finally look past the retail optics of “cheap beef” and confront the deeper problem: an industry where a handful of multinational corporations can dictate the price of a steer before it’s even born.

Why, on the news of beef imports from Argentina, boxed beef prices went up while live cattle prices fell

n October/November 2025, Trump announced expanded beef imports from Argentina to “bring down prices.” The market’s response was a masterclass in perverse incentives:

Live cattle prices fell. Traders priced in “more supply coming,” and bids for U.S. cattle slipped.

Boxed beef prices rose. Holiday and export demand kept the wholesale cutout firm. Packers bought cattle cheaper and sold beef dearer—a margin windfall.

If imports truly meant abundant supply, both prices should have eased. Instead, the middle captured the gap while the producer got hammered. The divergence wasn’t a fluke; it was a feature of a system where the choke point calls the tune.

What really happened

On the announcement, futures for live cattle dropped sharply. The logic: “More supply coming” (from Argentina) → expectations of weaker domestic cattle bids → producers panic → live cattle bids go lower.

Meanwhile, the wholesale cut-out value for boxed beef (especially Choice cuts) was already firm (or increasing) due to tight domestic herd numbers, strong foodservice demand, holiday demand, export interest. In other words, the downstream side (meat processors and retailers) saw a different set of signals: not immediate oversupply, but continuing demand pressure. Indeed, USDA’s Boxed Beef Cut-Out values rose around that time.

The divergence (boxed beef up, live cattle down) creates a “margin windfall” for packers: buy cattle cheaper, sell beef at higher or stable prices.

Ranchers get hit twice: their input (the live animal) is worth less, and they don’t share in the gain that processors get when beef sells at elevated prices.

Why that divergence matters

The stark split signals something is off in the supply chain alignment. If cattle supply is truly strong and heading toward import pressure, you’d expect beef wholesale to soften as well. The fact that wholesale beef stayed strong (or increased) while live cattle fell suggests capacity, buyer behaviour, supply chains or contractual terms are interfering with “normal” price transmission.

In the context of the Trump announcement, that divergence gave credence to complaints from rancher groups to sum it up “We’re getting hammered, packers are getting rich, and imports are being used as the excuse.” Because the packers were in the middle, they were positioned to benefit from the “live cattle side down” while the “beef side up.”

Not every dirty trick is illegal. Some are just “smart business,” depending on how elastic your ethics are.

Ways the meat-packers could (in theory) manipulate the market

Let’s break down what could be happening — different tiers of conduct: from aggressive but legal procurement practices to outright illegal collusion.

Hard-ball but (arguably) legal practices

Selective bidding or thinning cash markets. If packers choose not to compete aggressively in the cash market (say, reduce bids, delay purchases) then the “negotiated cash” benchmark (which is used in many formulas) drops. As more cattle fall into formula/contract pricing based off that benchmark, producers’ prices decline.

Formula contract design & timing. Packers write the formula contracts, set premiums/discounts, reference markets. They may schedule deliveries when they have capacity, push producers into times they prefer, or exploit windows when producers have less market power.

Grid terms that shift risk to producers. If packers set very tough quality/yield specs (with steep discounts for misses) then producers bear more downside risk. That reduces effective price for many, even though headline price may be the same.

Using capacity to pace kills/deliveries. If a packer has the capacity and inbound cattle, it may delay or reorganize slaughter schedules, thereby controlling the timing of when it needs cattle—and thus controlling when bids must be made. That can confer bargaining advantage.

Information advantage. By having more timely information about supply chains, exports, and wholesale beef demand, packers can act faster; producers are slower and less connected. That gap is legal (though troubling) and enables that packer leverage.

What would be illegal if done with anticompetitive intent

Price-fixing or bid-rigging. If two or more packers agree (explicitly or tacitly) to fix bids for cattle, or to fix prices of boxed beef or allocate territories, that violates the Sherman Antitrust Act (among other laws).

Market allocation or supply restriction. If packers conspire to limit slaughter or intentionally divert cattle to keep input prices low and beef prices high, that is anticompetitive. For example, the 2020/2021 lawsuits allege such behavior.

Giving “undue preferences” or manipulating markets under the Packers and Stockyards Act (P&S Act) of 1921. This law prohibits packers from giving special favours, apportioning supply, or manipulating prices in ways that disadvantage producers.

False or misleading contracting or deceptive practices. If a packer misleads a producer about the terms, changes the contract unilaterally, or uses contracts to trap producers unfairly, that may violate the P&S Act or other regulatory provisions.

Proving the latter requires documents, data, or a whistleblower. In a consolidated industry, that’s a tall order with career-ending consequences.

Why this matters to the rancher

Ranchers take the risks: weather, feed, rates, disease, biology. Yet they’re told their cattle are worth less because “imports might arrive next quarter,” while packers post record margins.

When producers work in a market where the buyers have dominant power, the negotiation is tilted. Even if outright collusion is harder to prove, the structural power and “legal but aggressive” practices can create an environment where ranchers get squeezed. Yourself raising calves, paying feed, standing risk, bearing fluctuations in weather, biology, markets — if the packer side dictates timing, price references, specifications, you’re at a structural disadvantage.

Consumers are paying more. Ranchers are earning less. If that sounds like the middle is winning, it’s because they are.

If one fire can crash cattle prices nationwide, the market isn’t free—it’s fragile.

A 5% Capacity Cut With a 20% Punch

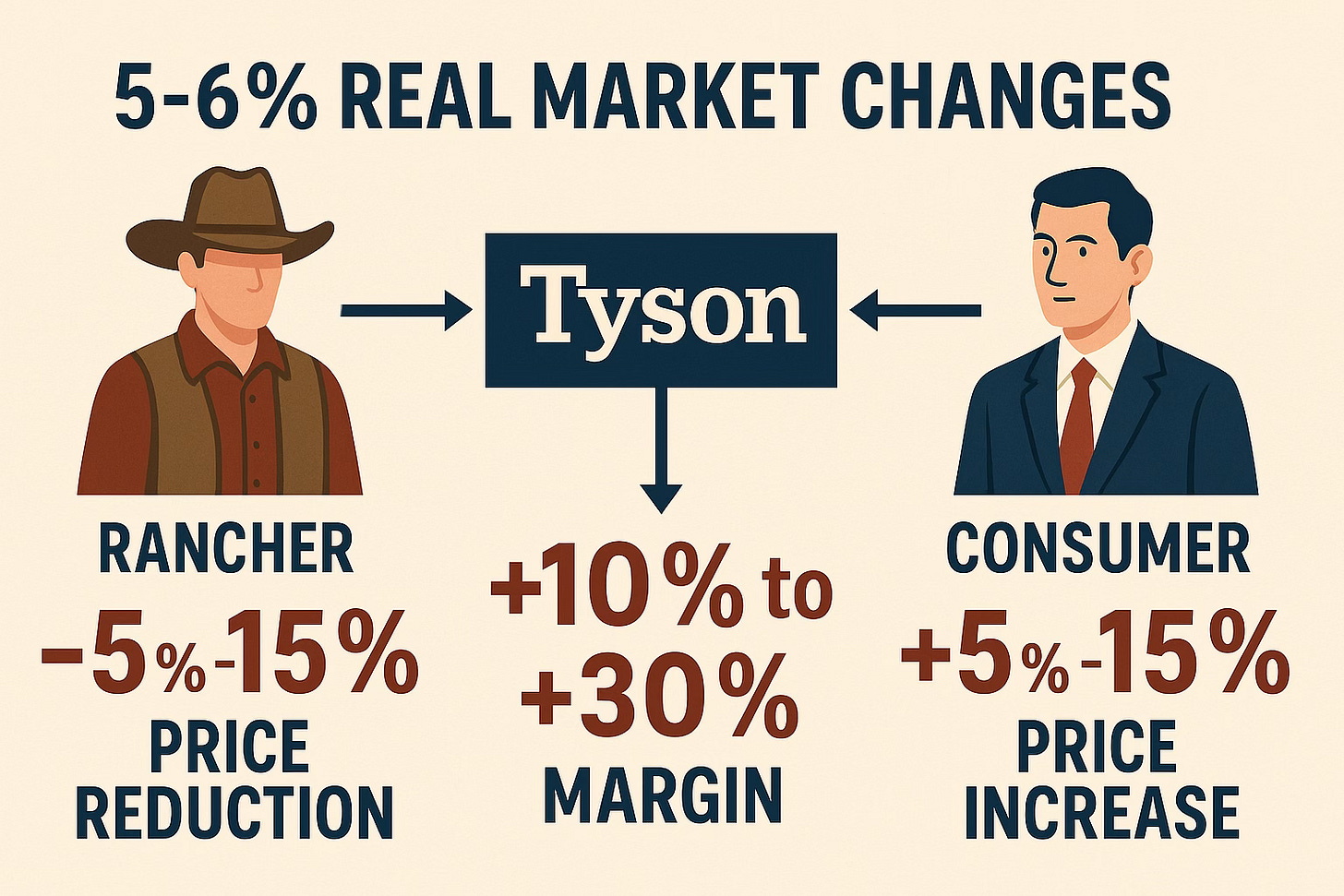

On paper, Tyson is pulling out about 5–6% of total U.S. slaughter capacity. That doesn’t sound catastrophic — until you realize how concentrated the industry is.

In a competitive market, a 5% hit is a bump.

In a four-company market?

A 5% hit behaves more like a 10–20% shift in pricing power.

Ranchers feel a 5–10% drop in real value for their cattle.

Consumers feel… nothing. Beef prices stay the same or rise.

Packers?

They see their spread fatten by 10–20% overnight.

It’s the closest thing agriculture has to a magic trick:

Take away capacity, and somehow the middleman profits.

What This Means in Cattle Country

Lexington was a competitive anchor.

When that anchor gets cut loose:

Ranchers lose bidders

Trucking distances increase

Shrink rises

Scheduling tightens

Negotiation leverage evaporates

Cash bids soften

And Amarillo’s shift reduction? Same story, different ZIP code: fewer kill slots, longer delays, and a tighter choke point for Texas, Oklahoma, and the Southern Plains.

Ranchers don’t sell cattle into a “national average.” They sell into a radius — and Tyson just shrank that radius for half a million square miles of cattle country.

Consumers Aren’t Getting a Break Either

We all know the script:

Rancher gets squeezed

Corporate packer “resizes” to improve margins

Grocery prices mysteriously don’t budge

If you’re wondering why your ribeye still costs $14.99/lb when ranchers are taking a hit… it’s because you’re not the target of the “savings.”

The savings went upstream.

The Spread: The Only Thing Growing Faster Than Corporate Press Releases

Pre-closure:

Rancher: $100 value

Packer: $140 beef value

Spread: $40

Post-closure:

Rancher: $90–$95

Packer: $140–$145

Spread: $45–$50

That’s a 10–20% margin jump without adding a single pound of efficiency, innovation, or infrastructure.

Just one big shutdown — and voilà.

“Market Conditions,” Or Just Convenient Timing?

Tyson claims cattle supplies are too tight.

And yes, the national herd is low.

But Nebraska’s cattle-on-feed numbers?

Slightly up from last year.

This isn’t scarcity.

This is convenience.

When supplies tighten, packers historically expand margins.

Closing high-capacity plants in the tightest part of the cycle amplifies that effect.

Call it whatever you want — but “market conditions” is the most polite version of the story.

**And Now the Part That Actually Matters:

How We Fix This Broken System**

If we want ranchers to rebuild the herd — and we absolutely need them to — the answer is not:

price-fixing

government manipulation

or another 600-page USDA “innovation framework” that fixes nothing

The solution is competition.

Real competition.

Local competition.

Competition that forces packers to earn the right to buy your cattle.

If we accept for a moment that the current system disadvantages producers, then what reforms or actions should be pursued to protect ranchers, restore competition, and better align the system?

Step 1: Build Mid-Size Regional Packers Again

We need hundreds of mid-size plants — not four mega-monuments.

Facilities that handle:

150 to 800 head per day

USDA or state inspection

Multi-species capacity

Modern cold chain

Lean overhead

Regional distribution

Not backyard lockers.

Not billion-dollar fortresses.

Real processors that force the Big 4 to compete again.

Give them tools:

Low-interest loans

Cold storage & wastewater grants

Equipment financing

Workforce pipelines

Tribal and cooperative ownership incentives

Do that — and suddenly ranchers have 3, 4, even 5 bidders again.

Everything changes.

Step 2: Deregulate Interstate Sales of State-Inspected Beef

This one is so obvious it hurts.

State-inspected plants meet equal safety standards to USDA inspection.

But due to a 1967 political compromise, their beef can’t cross state lines.

It is the dumbest rule in food policy, and it has:

Blocked small plants from scaling

Stifled rancher-branded beef

Prevented regional markets from forming

Locked processors into single-state cages

Concentrated power into the Big 4

Fix that rule, and overnight:

Regional processors can ship nationally

Ranchers can sell branded beef across borders

Small becomes mid-size

Mid-size becomes competitive

This is the cheapest, fastest reform — and the one big packers fear the most.

Step 3: Grow Rancher-Owned & Tribal-Owned Packing Capacity

If you want true stability, here it is:

Give ranchers ownership in the hook.

Give tribal nations ownership in the hook.

Give regions ownership in the hook.

A co-op packer doesn’t care about a quarterly earnings call.

They care about cattle flow and community survival.

They can:

Schedule kill days for producers

Ride out low cycles

Store beef during gluts

Capture cut-value

Keep bids honest

Support ranch families year-round

Ownership is the ultimate stabilizer.

Step 4: Give Ranchers Real Tools to Rebuild Herds

No price floors.

No government micromanagement.

Just common-sense resilience tools:

Fast drought insurance

Working capital tied to heifer retention

Tax deferrals for forced drought sales

Low-interest expansion loans

Forage and pasture insurance

Range improvement incentives

Ranchers don’t need handouts.

They need runway.

You can’t rebuild the herd if every drought forces liquidation.

Step 5: Preserve Existing Packer Capacity (Without Propping Up Tyson)

We don’t rescue mega-packers.

We keep infrastructure alive.

Ask packers to:

Downshift before closing

Cross-train to maintain flexibility

Repurpose lines seasonally

Maintain plants in operable condition

Permanent closures should be last resort, not first.

Step 6: Strengthen Cash Trade for Transparency

Not contracts.

Not formulas pegged to nonexistent markets.

Just one rule:

A minimum share of cattle must be bought in open, negotiated cash trade.

Because formula prices are based on that tiny sliver of negotiated trade — and if that sliver gets too small, price discovery collapses.

More negotiated trade = more transparency.

More transparency = more honest prices.

Honest prices = a rebuildable herd.

Step 7: Build Out Direct-to-Consumer & Branded Beef

The ultimate pressure valve.

If ranchers can:

Sell branded beef

Ship across state lines

Use regional packers

Access the cold chain

Market online

…then the commodity market suddenly has competition from all sides.

That stabilizes live cattle prices far better than any regulation ever could.

This Is the Free-Market Fix to a Rigged System

Let’s be honest:

Ranchers are not the problem

Consumers are not the problem

Tyson isn’t even the problem

The system is the problem.

Too big.

Too concentrated.

Too fragile.

Too beholden to quarterly earnings.

If we rebuild the middle — mid-size processors, co-ops, tribal packers, direct-to-consumer channels, interstate freedom for state-inspected plants — the whole system becomes:

More competitive

More stable

More transparent

More resilient

More profitable for ranchers

More affordable for consumers

And ironically…

Even Tyson benefits — because competition forces innovation instead of corporate plant-shuttering every time the cycle tightens.

The Road to More Beef

If We Want More Cows, We Need More Hooks — Not More Excuses**

Policymakers never seem to grasp the simplest truth:

You cannot rebuild the American cattle herd if ranchers are broke.

And ranchers cannot rebuild if they have only one or two places to sell cattle.

And those places cannot survive if they’re built for a herd that no longer exists.

The fix is right in front of us:

More hooks

More players

More routes to market

More regional strength

More competition

More freedom

That’s the future of American beef.

Not monopoly.

Not consolidation.

Not imported boxed beef.

Not contracts.

A real free market.

One where ranchers get a fair shake…

consumers get an honest price…

and rural America finally gets the respect it’s owed.

Ranchers Are Fighting Back

Ranchers in America are fighting an uphill battle. You raise the calves, bear the weather risk, invest in genetics, feed, time, pastures. You should get a fair shake in the marketplace. But instead you face a system where a handful of giant meat packers dominate, set terms, leverage capacity and timing, and can buy low while selling high — all to your disadvantage. The live cattle price you get is weak, even though consumers and grocery chains pay top dollar for beef.

The recent divergence — live cattle prices falling while boxed beef prices climb, especially amid the Argentine-beef import announcement — is a glaring symptom, not a fluke. It shows the packers sit between you and the final consumer, and they are capturing the gap. Whether or not all of that behaviour is illegal today, the structure clearly allows for producer exploitation.

Reforms are possible. We can restore transparency, strengthen enforcement, build alternative processing capacity, rethink import policies, and re-share value down the chain. If we fail to act, the result will be further hollowing out of U.S. ranchers, further consolidation of packers, and a weakening of U.S. food-system resilience. The rancher deserves better. The consumer may think they’re paying more for beef — and they are — but the rancher isn’t seeing that benefit.

America’s ranchers don’t want handouts. They want a market that pays fair for real work. The live-vs-boxed-beef divergence is not a rounding error; it’s a billboard flashing systemic failure.

It’s time to shine a spotlight on the packers and demand that the chain work for the people who raise the cattle, not just for those who process and package them.

If the DOJ does its job, we may finally see accountability—and a cattle market that works for the people who raise the beef, not just the ones who wrap it in plastic. Until then, when you see that $25 ribeye, don’t blame the rancher. Blame the middlemen carving up the market—one steak, one contract, and one ranch at a time.